“Il pane e le rose” di Andrea Iris D’Atri compie 15 anni e festeggia con la traduzione in lingua inglese

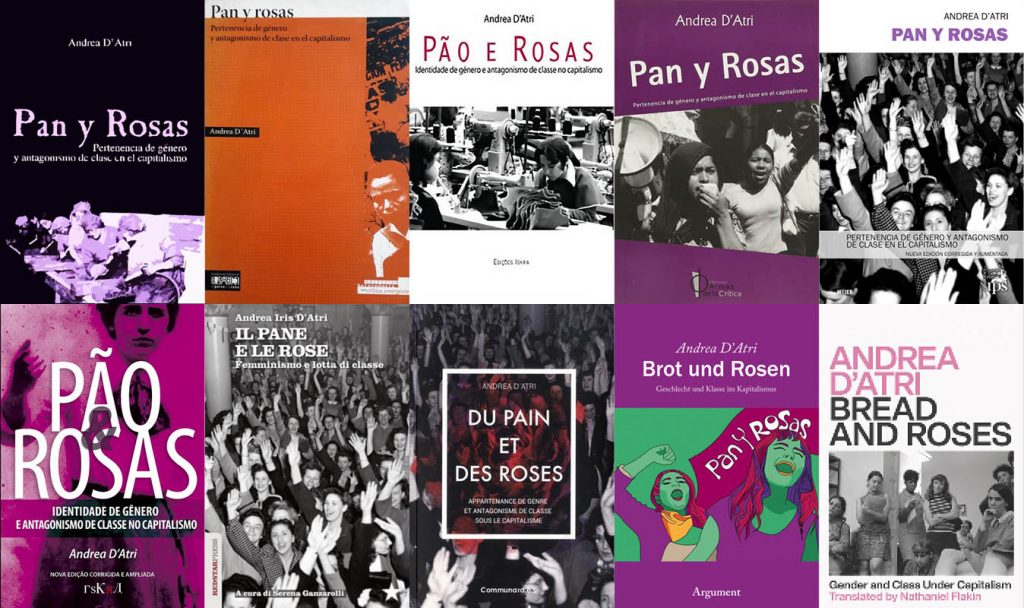

A quindici anni dalla sua prima edizione per la casa editrice argentina IPS e dopo aver dato linfa a un movimento femminista deciso a basare la sua lotta sul solido terreno della lotta di classe, “Il pane e le rose” di Andrea Iris D’Atri viene tradotto in inglese dalla casa editrice Pluto Press. La nuova pubblicazione si aggiunge alle edizioni già uscite, oltre che in Argentina e, per la Red Star Press, in Italia, in Venezuela, Brasile, Messico, Francia e Germania.

Da Leftvoice.org, riprendiamo il prologo scritto per l’edizione inglese da Andrea D’Atri, con la consapevolezza di come, ovunque, la crisi pandemica in corso si stia rivelando un formidabile strumento nelle mani delle classi padronali per colpire le già dure condizioni di vita dei lavoratori e delle lavoratrici, infierendo in modo particolare sulle donne:

– – –

To understand this, it is perhaps worth remembering that this book was originally published in 2004 in Argentina; at that time in the United States, Mark Zuckerberg and his friends at Harvard were launching a website to connect the university’s 20,000 students. Today, Facebook has over 2.3 billion users worldwide, besides owning WhatsApp, the leading messaging service, without which it is impossible to imagine this life in confinement, full of virtual classes, working from home, online entertainment, and video calls. In the midst of a global crisis and the dizzying events occurring every day, the year 2004 feels like it was more than a century ago.

To understand this, it is perhaps worth remembering that this book was originally published in 2004 in Argentina; at that time in the United States, Mark Zuckerberg and his friends at Harvard were launching a website to connect the university’s 20,000 students. Today, Facebook has over 2.3 billion users worldwide, besides owning WhatsApp, the leading messaging service, without which it is impossible to imagine this life in confinement, full of virtual classes, working from home, online entertainment, and video calls. In the midst of a global crisis and the dizzying events occurring every day, the year 2004 feels like it was more than a century ago.

Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism was later published in Venezuela in 2007, in Brazil in 2008, and in Mexico in 2010. In 2013, a new corrected and expanded edition was published in Argentina—that is the version that is presented here in English by Pluto Press. Although it was revised almost a decade after its initial publication, this text nonetheless pre-dates the international feminist wave of recent years and the great events the world is currently witnessing. This same version was translated and published in Italy in 2016, and in Germany and France in 2019.

***

When the first edition of Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism appeared in Argentina, we dared to propose that the relationship between the categories of gender and class be considered in the heat of history. We did this from the extreme South of our continent, and outside of academic circles. For this reason, although this book neither offers a detailed account of each of the infinite struggles of the international women’s movement, nor covers all the theoretical debates that traverse the movement, it does have the merit of presenting the hypothesis—15 years ago—that there will be no gradual, evolutionary progress toward the expansion of political rights and democratic freedoms for women.

At a time when feminist struggles were not on the front pages, this book argued that advances and setbacks in the struggle against patriarchy, within the framework of the capitalist system, coincide with periods of reforms, revolutions, or reaction. The idea that women’s struggles advance and retreat with the ups and downs of the class struggle runs through this book. And just as defeats of the masses meant that women and other oppressed sectors of society were silenced and forced to wait, revolutionary processes brought about unusual transformations, at an unexpected speed, of everyday life and social and political institutions.

This book does not contain an extensive discussion of the struggles for sexual liberation, about which we have written numerous articles. Nor is there an analysis of racism and the intricate web of oppressions that links gender and class with race, ethnicity, and nationality. Were we to rewrite this work today, having gone through great experiences of collective struggle and learnt a great deal, we would include an analysis of how capitalism organizes lives and bodies into hierarchies, shaping the working class in complex and heterogeneous ways. And without a doubt, the recent rebellions in the United States in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd and against the institutional racist violence of US imperialism—with Black women in the front lines of the mobilizations—would be a source of inspiration for such a new work on women’s oppression and the perspectives for emancipation. The emergence of a new generation of people who are taking up the perspective of a socialist society in the heart of imperialism would similarly inspire.

***

But when we wrote Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism, we were swimming against the stream in Argentina at the time: the social movements and the resistance struggles against the economic and political crisis at the end of the twentieth century were accelerating their steps toward assimilation into the political regime, abandoning their most radical aspects. Since that first edition appeared in 2004, the neoliberal discourse of “expansion of rights” has become established as the only possible horizon for social movements, including feminism. And paradoxically, in the midst of this retreat by social movements—and starting as a small minority—we not only published this book, but also made an effort to build a material force that would be able to incarnate the ideas reflected in it.

That is why, despite the important shortcomings and omissions in its pages, and even despite the major events that took place after the revised edition appeared in 2013, this book retains a particular value that is not an individual achievement of its author. If I mostly write in the first-person plural, this is because Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism is the result of an intense militant activity of swimming against the stream. Its pages originated in activism and struggles against exploitation and oppression; it was read and debated by young people fighting for the legalization of abortion, by women workers who took over their factories and got them running under workers’ control in the midst of a capitalist crisis, and by students who were not content to see their anti-patriarchal hatred be con-verted into a mere slogan or a passing fad.

This book’s journey, from hand to hand, allowed a small nucleus of revolutionary Marxist militants to set up the women’s group Pan y Rosas (Bread and Roses), with a perspective that is class-based, anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and anti-racist—in other words, socialist and revolutionary. Today, more than 15 years later, as this book appears in English, that original nucleus has transformed itself into a tendency with thousands of women workers in the service sector and in industry, with precariously employed women, with women who do not earn wages, and with young students. Our tendency has developed in Brazil, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Peru, Mexico, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Spain, France, Germany, and Italy.

Our tendency includes women workers from the multinational corporation PepsiCo in Argentina, who shut down production together with their male colleagues so the entire factory workforce could join the women’s strike against femicides in 2016. Pan y Rosas “Teresa Flores” also includes some of the healthcare workers, teachers, and young people from the “Front Line” in Chile, who occupied the squares and streets in the final months of 2019 to repudiate the murderous Piñera government. In the Spanish State, Pan y Rosas supports every single action of Las Kellys, a group of precarious cleaning workers at corporate hotel chains who are mostly immigrants from Africa and Latin America; these comrades have also written extensively about the debates on neoliberal feminism, the Right, and lesser-evilism in the imperialist European Union. Our comrades in Bolivia put their bodies at the front of the mobilizations that were repressed with blood and fire by the dictatorship of Jeanine Añez. In France, we are proud that the African immigrant women who went on strike against the company ONET, which exploits them as they clean the train stations in Paris, are our comrades; they are part of Du Pain et Des Roses alongside railway workers, bus drivers, and students. In Argentina, women shop stewards at the multinational corporation Mondelez (formerly Kraft Foods) who stopped the production lines to protest against a boss’s sexual harassment of a worker are also part of Pan y Rosas. In Mexico, Pan y Rosas is on the front lines of the struggle against sexist violence, alongside mothers and friends demanding justice for the victims of femicides in Ciudad Juárez. In Brazil, our Black comrades from Pão e Rosas are leading, together with the revolutionary Black organization Quilombo Vermelho, the struggle against the precarious working conditions that especially affect Black women—in a clear demonstration of the unity that exists between class, gender, and race for capitalist exploitation. They also recently published a book about racism and capitalism.

These are some of the thousands of women workers and students, lesbians, trans people, Latinx, people of African descent, immigrants, and indigenous people who form part of the international feminist socialist tendency Pan y Rosas. Today, as I write this preface to the English edition, some of them are in the front lines of struggle against the coronavirus in hospitals in Europe, the United States, and Latin America.

The construction of this militant international tendency has inspired the successive editions of this book in different countries, and at the same time this book has been an elemental pillar of this process of organizing thou-sands of women. Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism has become a tool to generate debates and to strengthen convictions, without dogmatism, while always remaining intransigent with the ruling class, the institutions, and the ideologies that maintain, reproduce, and legitimize patriarchal capitalist exploitation and oppression.

***

The current pandemic, which is spreading across the planet and leaving a trail of infections and deaths, has provoked interesting and controversial debates about the world that will come. Will nothing be the same as before, or will everything return to “normalcy”? Will this mark the end of Western capitalist democracy and the emergence of new totalitarian regimes, with an unprecedented increase in racist and patriarchal violence? Or, on the contrary, will humanity create new forms of self-organization and reorgan-ize society on the basis of egalitarian parameters?

Whatever happens, it will not depend on the coronavirus. It will depend, on the one hand, on the ruling classes and their governments who, in their zeal to protect capitalist profits, will attempt to load the costs of the crisis onto the shoulders of the working masses; and, on the other hand, it will be subject to the response that the masses are capable of giving in the face of these austerity plans. As long as the capitalists’ reactionary forces are not opposed by a collective social subject, one that fights for its own solution to the crisis that threatens us today, while remaining independent of all the capitalists’ political representatives and defending the perspective of a radical transformation, new and worse crises will occur in the future for millions of human beings.

This material force must be built. Young people in the United States, with Black people in the front lines, together with their Latinx siblings, fill us with hope that it is possible to move forward on this path. An anti-capitalist and revolutionary feminism cannot avoid this task, even less so as the new crisis we are entering highlights the deep contradiction between a parasitic class’s thirst for profits and the lives of millions of human beings, with women once again in the crosshairs.

If Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism can inspire young women workers and students of the new generation in the heart of US imperialism and other parts of the world to take this task into their hands—the construction of a force fighting for a society without exploitation, in which no human being is oppressed by another because of their gender, their skin color, their nationality, or any other reason—then I will feel proud that this book, published by Pluto Press in English, has served its purpose.

Buenos Aires, September 2020